BY ANNE CHECKOSKY

The western communities make good places for marijuana grow houses. That’s the conclusion of area law enforcement officials and why they want to arm the public with information about how to spot and report them.

“The size of the lots, the availability and privacy” make the western communities appealing to would-be growers, said Lt. David Combs, commander of the Palm Beach County Sheriff’s Office District 15 substation covering The Acreage and Loxahatchee Groves. “It’s the perfect place to do it,” he said.

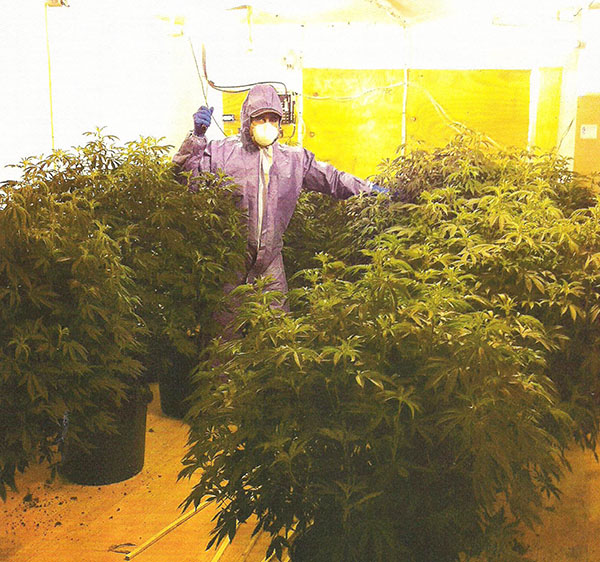

Last month, Alexa Ray of the Palm Beach County Substance Awareness Coalition and Edward Hunter, a PBSO Narcotics Division agent, spoke to residents at the Acreage library about the dangers of grow houses and how to identify them. Last year, the PBSO took down 62 grow houses.

Although many people think grow houses are victimless crimes, that’s not the case, especially if a homeowner is trying to sell a property and discovers that property values have dropped significantly because of a grow house in the neighborhood, Hunter said. And the opportunity to buy distressed properties increased after the housing market imploded in 2009, Combs added.

Grow-house operators are usually siphoning electricity illegally, Hunter said. The houses use about 300-kilowatt hours per day, according to the Electrical Distributors Association, which is 10 times the average household electricity consumption, Police Chief magazine reported in its May issue.

The large amounts of electricity used to power the lights needed to grow the plants can also cause power fluctuations, which can be problematic for neighbors. The water and high-humidity environment needed in these operations can also often lead to deadly mold left behind in the house, compounding an owner’s ability to sell it or repair it, Hunter said.

And operators are probably selling the marijuana to and in the community, Ray added.

So what are some of the signs that there might be a grow house on the block? One or more of the following: strong, strange odors coming from the house; multiple air conditioning units; unusual PVC piping; a pool pump present when the house has no pool; lots of security; excess water in the yard; covered windows; the property is left unoccupied for long periods of time; no mail delivery; and trash is seldom placed by the roadside.

Also, people coming and going at odd hours or for short time periods, Hunter said.

But he urged caution in jumping to conclusions. Many homeowners in the western communities value their privacy, which is why they choose to live in a semi-rural area in the first place, Hunter said. And tradesmen, such as owners of lawn care companies, for example, want to make sure their machinery is secured using chains and padlocks.

However, if residents suspect something’s wrong, they should call Crime Stoppers at (800) 458-TIPS (8477).

“It’s about a neighborhood protecting itself,” Hunter said.

Grow houses usually exist for about a year, and they can be remarkable in that they are often unremarkable, he said. Many of them are well maintained on the outside, and some may even have children living there.

One way to prevent a grow house from springing up in a neighborhood is to tell property owners that if they’re planning to rent their property, include language in the lease that clarifies inspections can and will be done on the property, Hunter said. And once the language is in place, it’s up to the property owner to enforce it.

Grow-house operators can and do take advantage of lax oversight from landlords, he said.

And while drug use among middle and high school students is down in Florida according to a Florida Youth Substance Abuse survey — 12.4 percent of students said they’d used in the last 30 days in 2012 vs. 13.4 percent in 2011 — the goal of Ray’s organization is zero drug use.

Partnering with the PBSO helps them get the message out. “We want to create a drug free Palm Beach County,” she said.